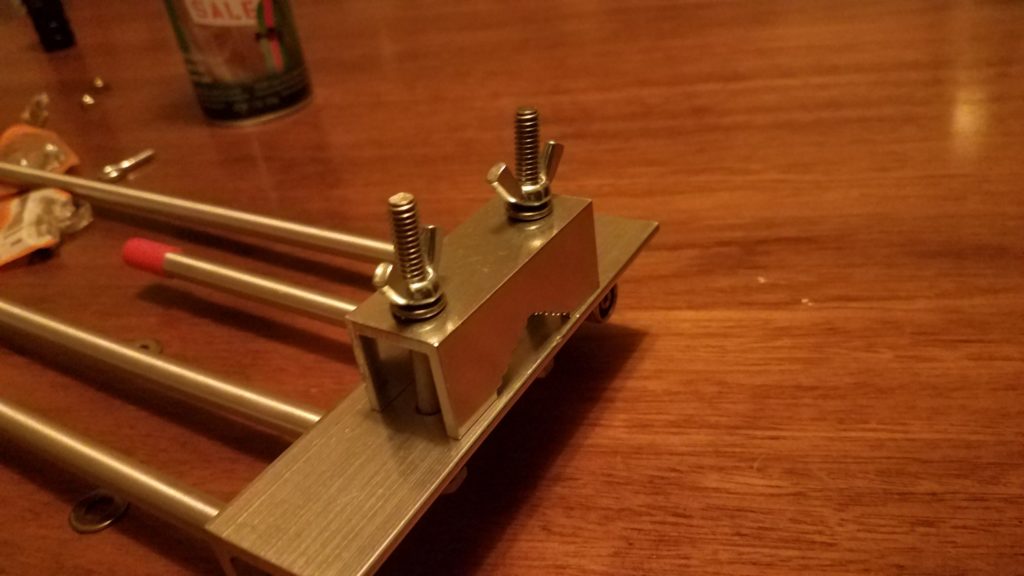

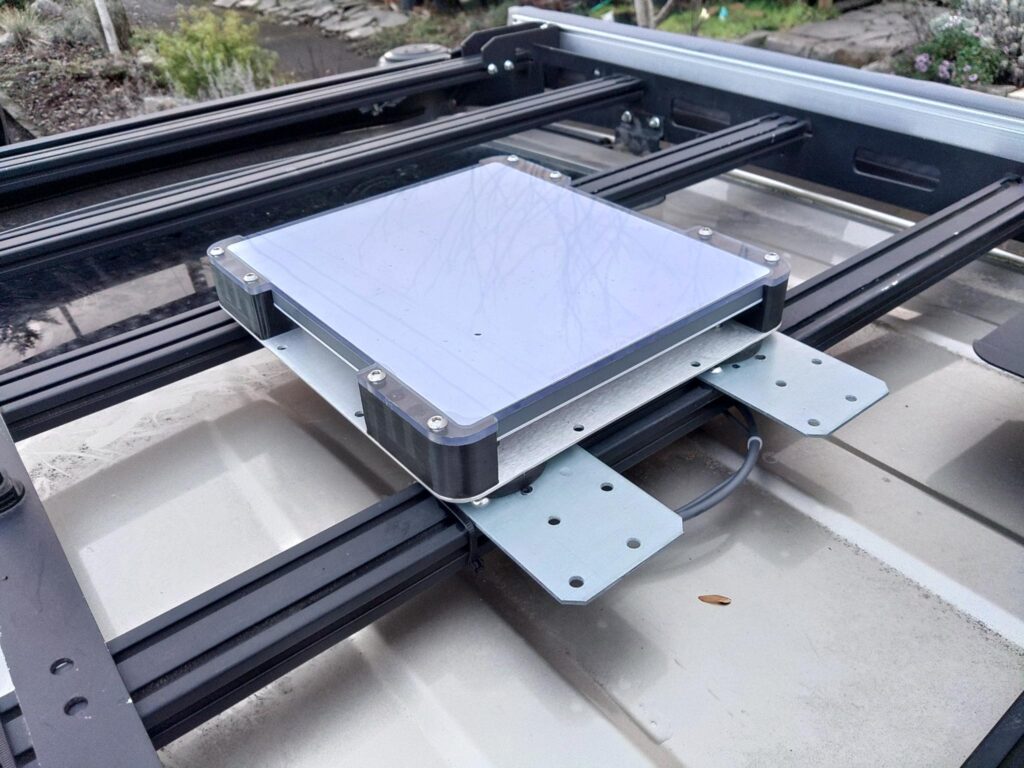

Welcome to another post. This one covers potential uses for the Starlink Mini in an emergency communications, gird down, or other scenario where Internet connectivity is required but unavailable using other means. There are a number of use-cases for it and there are also potential limitations of the device and its use during an emergency. Below is a photo of a Starlink Mini with an aftermarket protective case mounted to ferromagnetic plates (12ga Simpson strong ties) that are bolted to an aluminum roof rack on a vehicle. The screw hole pattern on the strong ties allows easy mounting to the roof rack with its supplied hardware.

What is a Starlink Mini?

The Starlink Mini is a standalone satellite terminal that provides high speed Internet with a clear view of the sky and active service. There are a number of Starlink devices created for various uses. The smallest and most portable offering is the Starlink Mini. It can provide advertised speeds of up to 100Mbps in ideal conditions and the cheapest roam plan for the mini comes with 50GB of data per month at a cost of $50 in the US as of this writing. Service can be paused at the end of the current billing cycle without cost to the user if it’s not needed and can be reactivated at any time. The terminal itself also costs about $450 and is currently on sale in the US. The Starlink Mini doesn’t require an external router like its predecessors and contains its own wifi router and a wired ethernet port. The device is configured and managed with a smartphone app and is designed to be fairly resilient against poor weather conditions. It includes a 15m power cable with 2.1×5.5mm barrel connectors, AC adapter that provides the unit 30v DC, a kick stand, and mast/pipe mounting kit. The Starlink Mini can also be used on a vehicle that’s in motion. The specifications for the unit can be found here.

How can it be used?

There are a number of potential uses:

- A standard Internet connection that can do everything a regular Internet connection can do: e-mail, social media, chat/voice/video messaging, etc.

- Using the device to facilitate wifi calling with standard cell phones. This is useful when there’s no cell signal and you need to contact emergency services or call for a tow, etc.

- Use for Internet-based navigation services such as Google Maps to get live updates on road closures, etc. in areas where there’s no cell service.

- An Internet gateway for AREDN to provide other users on the mesh with Internet connectivity when other Internet connectivity is unavailable to the mesh or is otherwise saturated.

- Integration with existing disaster response tools such as Winlink. The Starlink can be used as an Internet gateway for Winlink telnet transport, and its high bandwidth connection accelerate transfers that might be slower using RF Winlink technologies such as packet or VARA. Using a Starlink terminal also removes the need for a dedicated Windows host to continuously run a VARA software modem.

- Use as an alternative to AREDN when line-of sight to another AREDN node isn’t possible or when adjacent nodes are offline.

- APRS IGate Internet connection.

- A backup Internet connection when power is down or there is an Internet outage.

Things it can’t do:

- Replace GMRS or UHF/VHF communications. This is an Internet connection and doesn’t replace local comms and nets unless every team has one and reliable power for it. Even then it’s not sufficiently portable to communicate with individual teams when cell service is down.

- Natively connect to AREDN. A router and some configuration will be required to connect the Starlink’s ethernet port to an AREDN WAN port.

- Work well without a clear view of the sky, active service, and available bandwidth to communicate with satellites. Obstructions like trees, buildings, etc. will prevent it from working, and too many users or too few available satellites for a given area can negatively impact functionality, bandwidth and latency.

Real life use

I’ve only had the Starlink Mini for a couple months as of the time of writing but have already used it in two situations that weren’t testing or experimentation.

The first real use of the Starlink I had was a long road trip in poor weather (rain, snow, dense fog, high winds) where cell coverage was spotty at various points during the 5 hour drive. I was able to use the Internet connection to maintain contact with others, facilitate navigation, and stream music. On the way back there was an accident that backed up the interstate I was on for miles in both directions, and created hours-long delays. Despite not having cell coverage before I reached the stopped traffic I was able to avoid the wreck because Google Maps got a real-time alert and routed me around the accident using an alternate route automatically.

The second real use of the Starlink Mini was allowing me to continue working during an Internet outage. I was able to work normally including video calls and meetings after setting the unit up outside and connecting it to my network in a box (boost converter and router) that provided strong wifi coverage in the house. Even if I had lost Internet connectivity and power I could have run the network-in-a-box and Starlink on battery. See photos below of the network in a box.

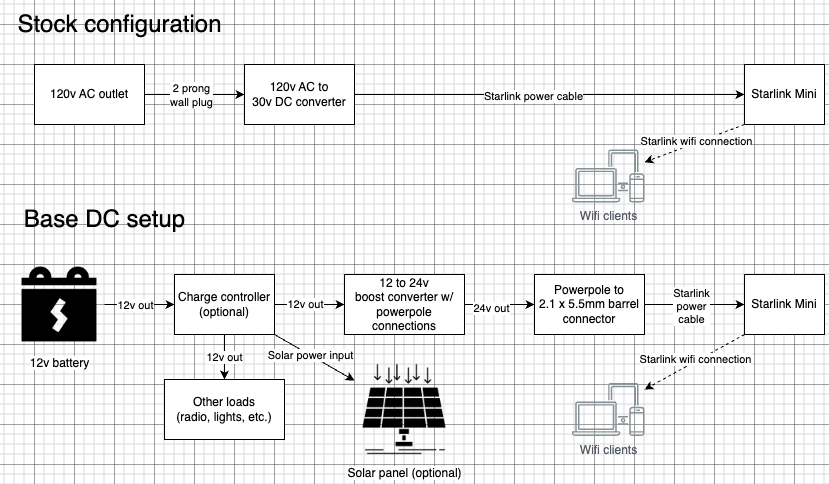

Adapting the unit to work without AC power

The first problem to solve with the unit is its reliance on AC power. You can connect the unit to an inverter or AC generator for power, but using a generator requires a steady supply of fuel and an AC inverter consumes a lot of power that’s used to boost your 12v DC batteries to 120v AC only to be downconverted to 30v DC in the end making it less efficient than a single step of boost conversion. I chose a boost converter that boosts the power from 12v DC to 24 DC and can provide up to 10A of current. While some power is lost in the boosting process this is much more efficient than a large voltage boost and AC conversion followed by a second downconversion to 30v DC. The 24v boost converter and that works with the 15m DC cable included with the kit.

It’s worth noting that the power cable is a small and there’s too much voltage drop over the length of the cable with 12v to run the unit as the required amperage at 12v is too high for the cable gauge, and the voltage is too low to power the unit. The higher voltage provided by the boost converter requires less amperage to provide the same wattage to the Starlink. Ohm’s law (Pwatts = Iamps * Vvolts rewritten as I = P / V using variable isolation) tells us that at a reference power level of 25w and 12v the small gauge cable has to handle about 2.1A over 15 meters, and that doesn’t consider voltage drop which prevents the device from functioning properly [25w / 12v = ~2.1A]. The same reference power level (also excluding voltage drop) at 24v requires the wire to handle about 1.1A [25w / 24v = ~1.1A]. Shorter cables such as the 5m aftermarket cables can run the unit on 12v but it does get fairly warm running on that voltage even with the shorter cable length and I wouldn’t recommend that especially in a warm environment as it may damage the Starlink Mini.

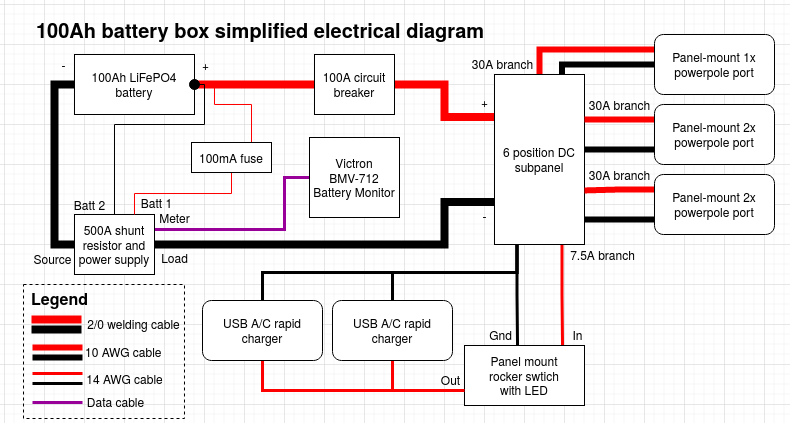

Power connection block diagrams for stock configuration and my base DC configuration

Exploded view of connections made in the base DC setup with the optional ethernet cable represented. From left to right, top to bottom is the Starlink Mini upside down showing the connection points, an ethernet cable with nothing connected to it, the DC power cable, 12-24v boost converter, and battery. It’s worth noting that the boost converter pictured here is for another project and is much larger physically and in terms of power capacity (20A) than the one used by me to run the device (10A) in the field and is there as an example.

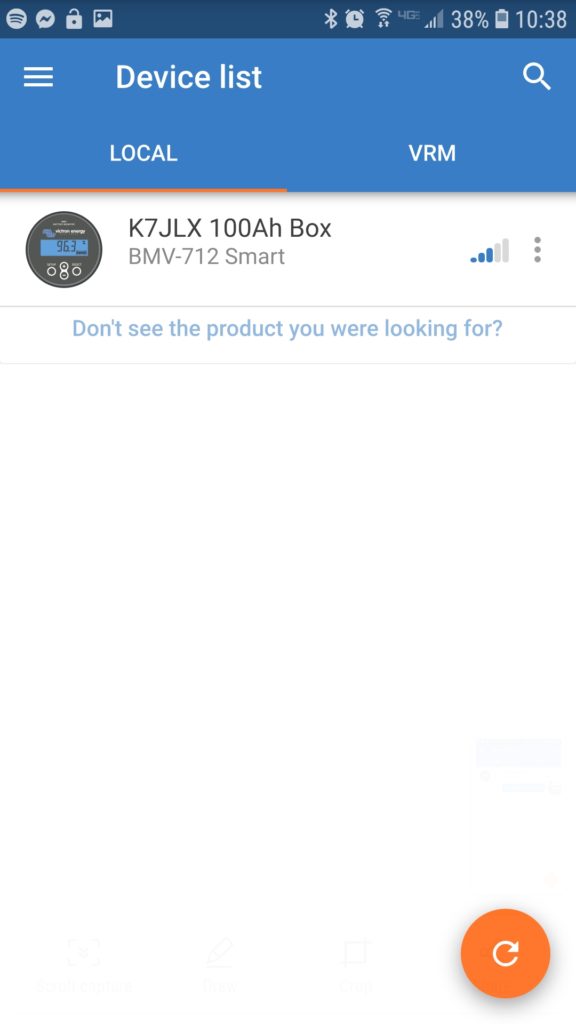

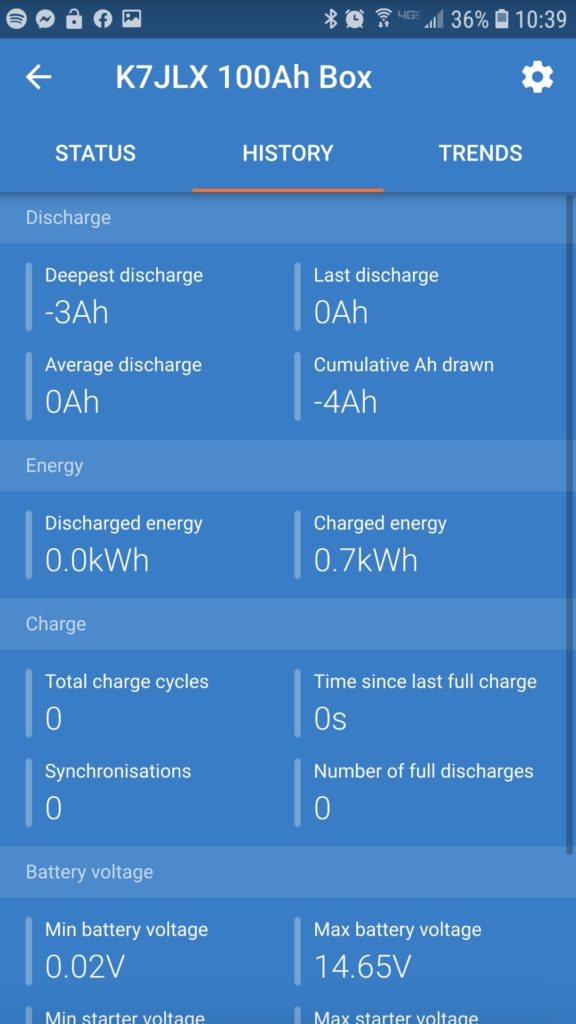

Network in a box

The network in a box is my solution for making the components that run the Starlink from a battery more compact, portable, and protected from dust and rain when in transit. Having all that set up ahead of time reduces the amount of time needed to fumble around making connections under duress or in adverse conditions and reduces the likelihood of human error causing damage to various components given the differences in voltage between the Starlink Mini and all other components. After dust and rain caps are removed from the ports it is no longer protected from the elements. There is a section that details the network in a box’s wiring, ports, etc. near the bottom of the post. The picture blow shows the system connected to power the Starlink, connect ethernet to the router included in the box, and has the optional ethernet connection to the laptop hooked up. Another advantage of having a separate network in a box is that the router running OpenWRT is more configurable than the Starlink Mini itself and supports features like firewalls and VLANs. These features can be important when integrating the Internet connection with an AREDN mesh node.

Optimizations, accessories, and considerations

Power consumption and snow melting capabilities

The unit tends to use about 25w of power at the unit (not including power used boosting the voltage) while running without the snow melt system running. I’ve intentionally disabled the snow melt functionality to prevent unwanted spikes in power usage. Most scenarios I’ll use the unit in involve me being outside or near the unit so clearing snow from the unit by hand shouldn’t be an issue. With the additional thickness of the protective polycarbonate layer and small air gap between the two I suspect the snow melting functionality would be less effective anyway.

Cable kits and cabling considerations

I have two power cables for the unit – one aftermarket 5m cable and the 15m cable included with the kit. The 5m cable is more efficient and has a lower voltage drop than the 15m one and can be used when the unit doesn’t need to be far from me to get a clear view of the sky. It’s also nice to deal with only 5m of cable unless you actually need the 15m length to fit your situation. These power cables are 2.1 x 5.5mm barrel connectors with a center pin positive configuration with weather resistant boots on both ends. I did splice powerpole connectors inline with the Starlink DC cable so I can connect directly to a 24v boost converter that has powerpole ends installed if necessary. It removes the need for multiple adapters in some situations, but allows you to connect to the native barrel connector in others.

In order to connect the unit to AREDN or any other network you might want to run that can’t run as a wifi client you’ll have to purchase a special weather hardened ethernet cable that has a boot that seals the port on the unit when the plug is removed from the port. I have an aftermarket 5m cable to match the power cable’s length and purchased a 15m cable from the Starlink website for about $30. This pairing of cables enables me to optionally connect the unit to a router or switch and can allow me to move the wifi access or cabled access closer to my work area which might be necessary if the position of the Starlink unit prevents a reliable wifi connection.

The official and aftermarket Starlink ethernet cables I purchased have proprietary RJ45 ends with a weather resistant boot that protects the jack from water and dust ingress. I ended up cutting one end off of each ethernet cable and installing a standard RJ45 end for compatibility with standard ethernet jacks found on most consumer routers and switches.

Protecting the unit from adverse conditions and adding additional mounting capabilities

While it’s not explicitly necessary to deploy the Starlink Mini physically hardening the unit with an aftermarket case could also be useful in some situations and has some advantages, but has costs in terms of additional bulk, weight, and safety considerations in my configuration. The surface of the satellite terminal that faces the sky can be scratched, gouged, or otherwise damaged by branches or sharp objects. Third party manufacturers make cases for the unit that allow it to operate in rougher conditions than it was designed to and add some advantageous security properties along with additional mounting options.

The case I purchased from Striker Fabrication has a handle, aluminum baseplate, and polycarbonate lid for the top of the unit. This allows me to mount it to my vehicle when offroading or on the highway as branches might sweep the unit or debris may strike it resulting in damage to the sky-facing surface. I added four 65 pound magnets with M6 threaded posts and lock washers to the corners of the unit that allow me to mount it to any magnetic surface such as a vehicle roof or hood. The holes I used to mount the magnets can also be used to bolt the case to any other permanent or semipermanent mount point using M6 screws. The aluminum plate under the case is compatible with the mounts that come with the Starlink Mini so it can be placed on a pole or on the ground with the included kickstand without needing to be removed from the case.

I can also loop coated wire rope through the aluminum and roof rack and secure it with a pad lock to ensure that a branch strike won’t sweep the unit off the roof of my vehicle entirely while in motion. It also acts as a theft deterrent for when the vehicle is unattended. I have two other pieces of coated wire rope that are 2.5 feet short of the full length of the power and ethernet cables to make theft of the deployed unit more difficult and to provide strain relief if the cable is pulled or tripped on when deployed on the ground. If the coated wire rope is anchored to a secure point on the terminating end a trip or pull on the cable is less likely to result in the power and network cables from being ripped from the Starlink Mini or attached power supply and network equipment. A pulled network or power cable can damage other equipment such as batteries, network hardware, or laptops by pulling them over or off of elevated surfaces. The Starlink unit will hopefully be the part that is harmlessly dragged by the coated wire rope due to its relative light weight and the other end of the cable being secured. The choice of coated wire rope was made because of its relative strength and light weight. The coating on the wire rope prevents scratches on painted surfaces, allows it to slip past snag points more easily when pulled, and aids in corrosion resistance.

Magnet safety warning: The four 65 pound magnetic feet provide a total of 260lbs magnetic pulling force. These will unexpectedly stick to metallic objects, pick up sharp bits of metallic grit and filings that can damage paint, and they will stick to metallic objects in your pockets or in your environment while being carried. Be aware of your surroundings and exercise caution. The magnetic mounts can also cause the case to crush your fingers when the case sticks to a metallic surface. Don’t ask me how I know. It’s worth noting that with this configuration it can be difficult to remove the device from a surface that it’s stuck to. Exercise caution when using powerful magnets – especially when handling the unit, sticking it to a surface, or removing it from something it’s stuck to. When it comes loose it does so quickly and you can unintentionally throw the unit when it releases. Again, don’t ask me how I know.

Factors effecting operation and Internet bandwidth

Internet connection speeds vary due to a number of factors including the location of the unit and whether or not it has a clear view of the sky according to its specifications, the number of users connecting to the satellites the unit is also using, and wifi connection strength.

Full kit photos

The following photos show the full kit. Most components of this kit are fully optional. The only real requirement to run the unit is the 12-24v boost converter and associated connections along with an activated Starlink Mini and a clear view of the sky. The picture shows the 15m cables power and network cables that are zip tied together every 18 or so inches since they’re almost always used by me at the same time, but the ethernet end doesn’t have to be connected if there’s a reason not to. The 5m cables are separate because I can usually use the Starlink Mini’s wifi at close range and handling more cable isn’t usually necessary but I have the option to deploy the second cable if needed. This kit includes aftermarket water + dust resistant caps on the Starlink end of all cables to protect the cables from water and dust during deployment and breaking down in adverse conditions. The bottom row on the left shows the AC power adapter, pole mount, and kickstand when opened, but not attached to the bottom of the unit. The pole mount and kick stand snap into the underside near the network and power cable ports and the enclosure is fully compatible with the mounts as well.

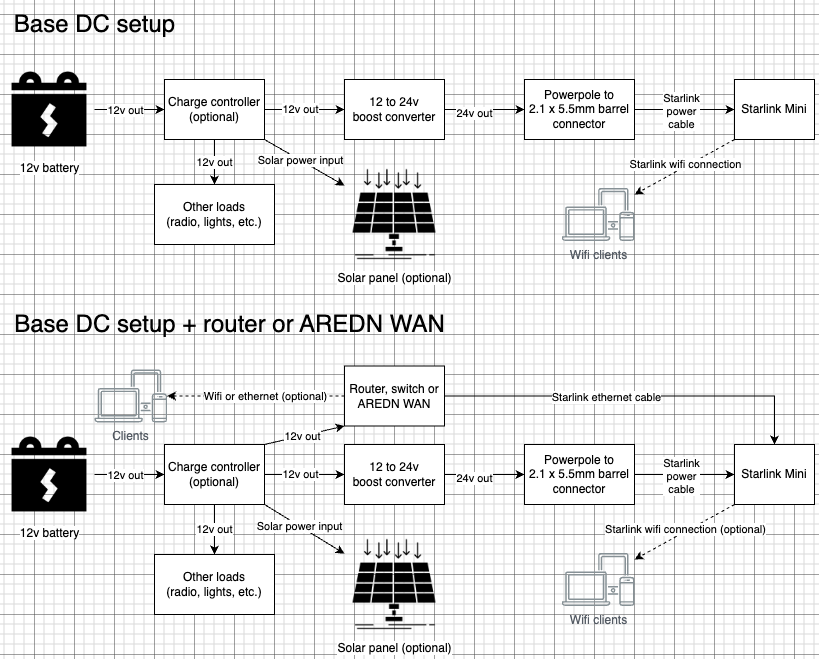

Base configuration and added router / AREDN node

The following block diagrams depict a basic DC power setup with optional solar and battery charge controller as well as a configuration that connects the Starlink Mini to a router or AREDN node. Since AREDN nodes are functionally routers the connection principals are basically the same. See the above photo of the network in a box setup to see what the wiring looks like with a connected router.

Network in a box detail and photos

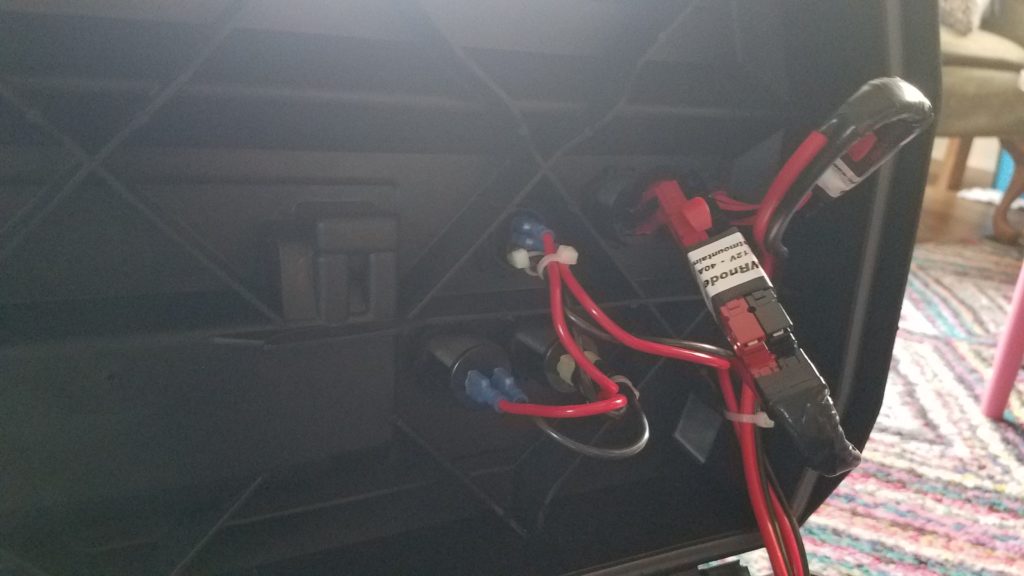

Exterior detail

The gallery below shows the exterior of the enclosure including ports and power controls. As noted previously this unit has port covers designed to protect the system from dust and moisture in transit. Once the ports are opened the unit is vulnerable to dust and water ingress so it requires some care after being deployed. The bottom of the unit has non-slip pads stuck to it because the enclosure’s bottom is slippery and there is a chance the screws that hold the boost converter could scratch surfaces so those non-slip pads also provide a degree of separation between the screws and the surface the unit is sitting on.

Power is provided by a single powerpole connector wired in a right-hand-red configuration, and power to various components is controlled by two pushbutton switches with LED power indicator rings. These physical switches are installed for easy control of loads and to prevent parasitic power draw when components shouldn’t be running.

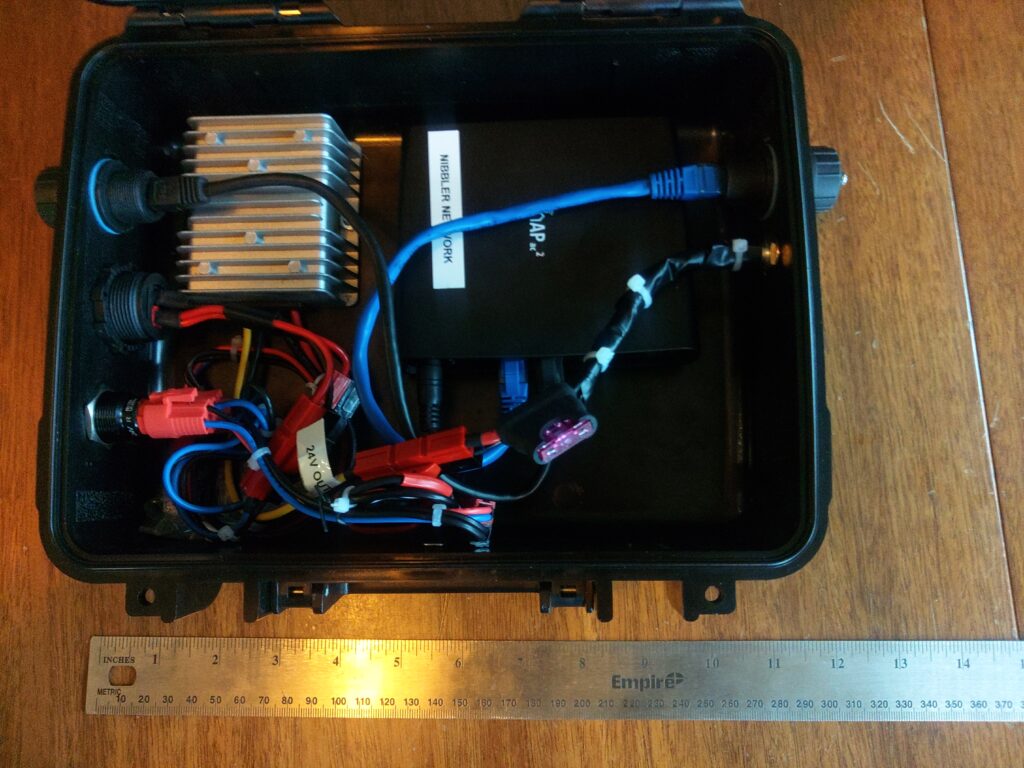

Interior detail

The inside of the enclosure is shown below. The major components are a DC 12-24v boost converter, a Mikrotik hAP2 router running OpenWRT, an open source router firmware, switches, fuses, power wiring, and network connections. The unit includes a bag of spare 1A and 3A fuses that are stored inside the case for field repairs. The router is connected to the bottom of the enclosure using velcro so it can be removed as needed. All power connections in the case are also powerpole so in the event some component fails and needs to be replaced, bypassed, or reused elsewhere on the fly there’s minimal effort, tools, and wire splicing required to make changes.

Starlink Mini network engineering details

The Starlink unit is configured from the mobile app, but the base networking characteristics of the unit are as follows:

- The Starlink Mini has a built-in router and dual-band wifi access point as well as a weather-hardened proprietary ethernet connector that supports provides 10/100/1000Mbps ethernet. This connector is a modified RJ45 jack wired using the EIA 568B standard. The official Starlink ethernet cable is outdoor rated Cat6 shielded twisted pair.

- Starlink service provides native IPv4 and IPv6 capability.

- There are 2.4 and 5Ghz wifi networks generated by the unit itself and these can be disabled or split into different SSID based on frequency if required for certain devices that have issues selecting the correct network.

- The unit is configured to hand out IPv4 and IPv6 addresses using a local DHCP server runing on the Starlink Mini when it’s in the default operating mode (not in transparent bridge mode).

- The default IPv4 address space is 192.168.1.0/24 and the built-in router uses 192.168.1.1 for its address and the default gateway.

- I don’t think there is any web UI to configure the router on the Starlink Mini. This isn’t the case with other Starlink products I’ve worked on. The mobile app or Starlink website is required to configure the Starlink Mini.

- Access to GPS location, telemetry data, and configuration endpoints are available via gRPC endpoints hosted on the Starlink Mini unit. These gRPC endpoints may also be the mechanism that the app uses to configure the device. See Sparky8512’s project for example code that interacts with the gRPC endpoints.

- Unlike its predecessors it can’t be powered using power over ethernet. The DC power cable is required for the Starlink Mini to power up.

- The unit can be set up in transparent bridge mode and any wired device connected to it is required to run its own DHCP client to get a WAN address from the upstream Starlink network. In order to switch back from transparent bridge mode the unit will have to be factory reset using the reset button on the under side of the unit.

- All wired and wifi hosts connected to the unit are dropped onto the same subnet and can communicate with each other directly. There doesn’t appear to be any client separation inside the LAN.

- The advertised WAN bandwidth is up to 100Mbps but I and others have seen speeds in excess of 100Mbps in certain locations and conditions.